by Lillian Leptos

The Year 7 STEAM classes are bursting with ideas and enthusiasm in the rockets unit. The students worked through the theory units, learning about forces, thrust, and aerodynamics, centre of pressure and centre of mass. Then came Phase 2 and the tricky part of applying this knowledge to the design of their own water rockets.

Teams of three had to decide which of the three possible designs they would then take through to Phase 3 and build it in a model.

Phase 4 was the field testing of each model and like true scientists, the students used the test results to modify the design and re-test.

This was where some discovered that complicated two-stage models that jettisoned parts of the rocket as it rose may have had some inherent design problems. It was also at this stage that other groups discovered some construction flaws.

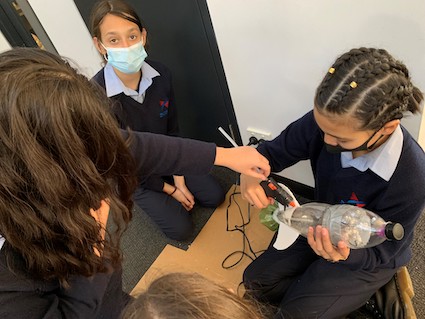

Repairs were made using hot glue guns, but in some cases, the glue was too hot and melted the rocket’s plastic bottle body, allowing air to escape and leaving the craft dead on the launchpad.

So fins were modified in size, shape and number and adjustments were made to the amount of water the rockets were loaded with. As air was pumped into crafts, leaks were exposed and ways found to plug them.

As a STEAM teacher, watching the students repeatedly move between launchpad and classroom for changes and modifications, was the most exciting part. It was here students’ critical and creative skills were most apparent.

Some rockets soared stably, reaching distances of 50 metres and heights of at least 25 metres. Some spun out of control and needed major adjustments to the weight and its placement. One spectacular launch ended in catastrophic failure as it totally disintegrated on landing.

From a STEAM teacher’s perspective, every rocket was a success as the unit’s purpose was to practice the design process and to verbalise and use problem solving.